Read the Charter of Independence here.

The Australian-dominated Imperial Camel Corps was a strange legacy of the Afghan cameleers who were brought to Australia in the 1870s, who opened up the Outback with the aid of a sturdy flock that could cope with the tough conditions.

The camels flourished, but relations between the Afghans and the local community were tense, escalating to widespread discrimination and violent attacks. Out of the melee emerged Abdul Wade, a successful Afghan camel merchant who wanted to give Australia's military a gift of 500 camels for service in Egypt in WWI.

It was an extraordinary offer that came from deep patriotism, but feeling against Afghans was high. ARON LEWIN has compiled this special report on a little-known slice of Australian history.

In the 1870s, Australia wanted and needed camels, and they brought in Afghans along with them to keep the difficult charges in order.

Camels, though these days classified as a pest, were once a valuable commodity that made exploration and economic development possible in arid and previously impenetrable regions of Australia.

[gallery type="slideshow" size="full" ids="5611,5612,5614"]

Coming about 50 years before the development of roads in the 1920s, they superseded horses and mules as the preferred mode of transport in the Outback. They could run further, carry significantly more, were cheaper and more able to adapt to the dry conditions in Western Australia.

The Victorian Exploration Expedition determined that the camels would be useless without their native drivers, so cameleers were brought in too.

Between 1870 and 1920, 2000 cameleers and 20,000 camels were imported predominately from western Asia to Australia. Although they were recruited from a number of regions and identified with a variety of different cultures, the cameleers were collectively labelled as Afghans.

Almost exclusively Muslim, most of the Afghans segregated themselves in "Ghan towns" across Australia – settlements on the fringe of town primarily comprising huts and small houses. They were reputedly hard workers who, as a community, strived to raise funds so they could build small mosques, Islamic schools and halal butcheries.

Although they arrived in Australia as cameleers, the Afghans quickly made their mark as hawkers, miners and herbalists. They worked closely and formed a kinship with Indigenous Australians. And they left a lasting legacy – according to the 2011 census there are 1140 people who identify as Aboriginal Muslims.

Despite the important services provided by the Afghans, the local population perceived them as a threat.

Gathering in pubs across Australia, the locals would talk about these dark and mysterious men who wore turbans and dressed in “coloured pantaloons and tunics” (Hanifa Deen, Ali Abdul v the King). Widespread fear began to circulate that these immigrants would marry local women, spread diseases and dominate the commercial market by employing cheap labour.

There was also concern over the establishment of mosques and halal butcheries in the townships and fear over the proselytising of Islam.

An "anti-Afghan" movement began to emerge at the beginning of the 20th century. The disquiet of the local population was being voiced in editorials and letters to the editor across the country.

Author and historian Hanifa Deen says in her book Ali Abdul v The King (UWA Publishing, 2011) that Muslims were also fearful of the Australians.

“From a ‘Mohammedan’ point of view … Australians were loud and undisciplined, given to swearing and drinking enormous quantities of beer after which they kicked up a ruckus and fell down drunk. They gambled and they smelt because as everyone knew, they hardly ever bathed – or maybe it was because of the swine flesh they enjoyed eating.

Also they were not a very God-fearing people; you often heard them calling out for their lord at the most odd times: ‘Jesus Christ!’ they yelled if they hit their thumb with a hammer or if they got angry with you. Religiously speaking, they were a peculiar lot of kafirs (unbelievers) who worshipped idols in their church

… How could you warm to such a race of people? But then you were not in Australia to make friends. Remember the old saying about white foreigners, ‘the Feringhi [white foreigner] in their religion and we in ours’ Stick to your own kind, make as much money as possible and return home a hero!”

Restrictive legislation and epochal events also helped to exacerbate hostilities between the two communities.

The creation of the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (the White Australia policy) limited the ability of Afghans to come to Australia. A camel tax outlined in the 1902 Roads Act that restricted movement and trade interstate was viewed as viciously unfair and the 1903 Naturalisation Act disqualified Afghans already in Australia (and natives from Asia, Africa and the Pacific Islands) from becoming citizens.

Consequently, most of the Muslims living in Australia fled back to their native countries and the ones who stayed were seen in the eyes of both citizens and the law as pariahs.

The onset of The Great War in 1914 created a crisis of identity and allegiance for many of the Muslims living in Australia.

Australia was fighting against the Ottoman Empire whose Sultan (and Islamic Caliph at the time) Mehmed V ordered all Mohammedans aged between seven and 70 to engage in a holy war against the allied states. In conjunction with this, poor working rights, restrictions regarding immigration of family members to Australia and the general unease of the Australian population towards the Muslim community caused much exasperation.

The following extract reporting on a speech given at a Muslim group prayer in Shepparton for an Allied victory highlights the difficulties that they faced

“Why do Australians call us black-fellows, when we belong to the same Empire, are fellow subjects, and are fighting under the same flag for the King, and our united empire?

We are in this war, giving up our lives the same as Australians, and fighting with equal courage and loyalty. Why, then, do they forbid us to come to Australia?”

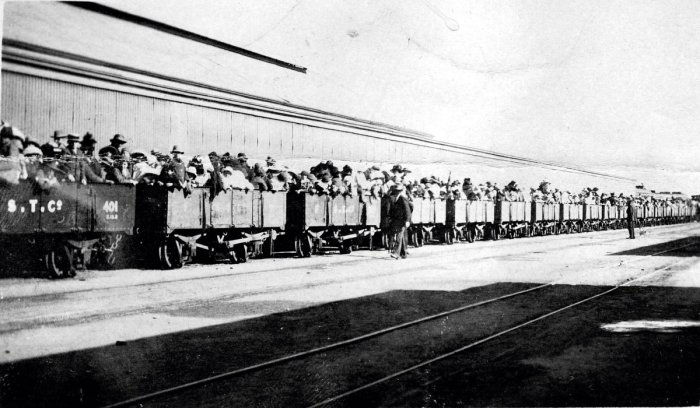

Tensions reached a boiling point on New Years Day 1915. Under a Turkish flag, two Afghans, Mullah Abdullah and Badsha Mohamed Gul, entered a picnic train carrying 1200 passengers in Broken Hill with a 45-calibre, single-shot rifle. They killed four people and wounded seven more before being shot by police.

It is reported that Mr Abdullah was inspired both by the jihadist message and an inability to receive a license to slaughter and prepare meat in accordance with Sharia Law.

In response, a mob burned down the Broken Hill German Social Club and intended to attack a mosque in the Ghan town. however, they were prevented by soldiers and police.

Abdul Wade was a pioneer of the camel trade in Australia; he was colloquially known as "Prince of the Afghans" and "The Afghan King".

Moving from Afghanistan to South Australia in 1879, Mr Wade quickly earned enough money to buy eight camels that he loaded and drove around town. He began to talk to other Afghan drivers and by 1893 he was importing camels from Afghanistan.

Two years later, Mr Wade founded and managed the Bourke Carrying Company, which went on to become the biggest camel company in Australia. He owned breeding stations in Wangamana and Artesia and, by 1905, it is reported that his company owned between 600 and 700 camels.

A large man “with teeth white enough to make you wish to be an Arab”, he worked hard to fit in, reading voraciously and endeavouring to cultivate a charming and gentlemanly persona. He was also a raconteur who frequented bars, restaurants and clubs as often as possibly.

A tribute to Abdul Wade was written in Broken Hill’s Barrier Miner newspaper.

“Abdul Wade is one whose name at least tens of thousands of people have heard and read a good many times these last few months.

“[He] strikes you at once as one upon whom trouble rests lightly, and one who finds this world a very good place indeed to live in. He talks volubly; and though there are some letters of our alphabet with which he struggles vainly, he expresses himself remarkable well.”

He strongly identified himself as an Australia and in 1902 he was naturalised as an Australian citizen.

In conjunction with his entrepreneurial spirit and desire to assimilate, Mr Wade tried to establish some of the Muslim customs and traditions in Australia. He bought land at 20 Little Gilbert St in Adelaide, and became the rightful owner of the Adelaide Mosque between 1890 and 1920.

There are anecdotes provided by Christine Stevens in her book Tin Mosques and Ghan Towns and the Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (respectively) which highlight the amusing way with that Mr Wade observed halal

Despite this, his reportedly rough treatment of camels and poor treatment of Afghan staff was the cause of some conflict with both the Afghans and the wider community. He had a bitter dispute with rival cameleer Gunny Khan over reports that Mr Wade brought Afghans to Australia with the prospect of jobs, and consequently failed to offer them work.

Mr Wade also received no support from the Australian Workers Union. They disallowed wool shearers from using the Bourke Carrying Company for the purpose of freight transport on account of the fact that “the union will not consider Afghans as members [and] … will not allow unionists to work in conjunction with Afghans”.

Nevertheless, camels were in high demand for both private companies and the Australian military.

In January 1916 the Imperial Camel Corps (ICC) was established and employed in Egypt and Palestine to deal with the pro-Turkish tribesman and Arab revolt respectively. Four companies were established and, according to the Australian War Memorial, they were comprised primarily of tough and troublesome Australian, British and New Zealand soldiers recuperating from the battle in Gallipoli.

The brigade would travel to the battle via camel and, on arrival, would fight on foot as infantrymen.

The effectiveness of the ICC is reflected in this article published in the Geraldton Guardian on May 31, 1917.

“Their work is arduous and monotonous in the extreme, and consists mainly of conveying water rations, fodder and ammunition to the mounted column that has hurried Johnny Turk over the border of Egypt into his own territory again.

Right well has the job been done, and but for the Camel Transport Corps the campaign would have been impossible. Day after day, week after week, huge trains of camels loaded with war materials, attended by Arab drivers and superintended by the C.T.C., have moved across the blinding, shifting desert.

… Personally, I look on them both as evidence of the wonderful spirit of our men, who, after a year of fighting over one of the most arid deserts of Africa, are able on reaching the other side to behave like big joyous schoolboys seeing only the bright side of life. ”

Although the record books show the ICC in a positive light, during its incubation period it was in need of assistance, the Sydney Zoo being its only real resource. As a highly successful merchant, Abdul Wade saw the opportunity to lend his assistance.

During August 1914, Mr Wade forwarded a letter to the minister of defence, Senator George Pearce, offering the Commonwealth Government the services of about 500 camels. Despite the hardships he and the Afghans suffered from the unions, he also promised the Pastoralist Union of New South Wales two horses for military purposes.

In June 1916, it is reported that the ICC accepted six of his camels. It is not clear why the Australian military did not accept more of his camels or employ more Afghan camel drivers, however it could be speculated from old newspaper articles that this was an opportunity to showcase the superiority of White Australians over the Afghans and Indians in the tasks that they mastered.

What is clear from the records is that Mr Wade’s offer was not purely in order to spruik his own business. Rather, he was devoted to advancing the Australian war effort.

In addition to his donation, he tried to enlist his son to the Australian army. Despite being an Australian citizen for more than 40 years, he was unsuccessful. He vented to the local newspaper, The Scone Advocate.

“In the eyes of the Government … I am guilty of the unpardonable sin of having been born in Asia, and although I have spent practically all my life in this country, I am denied the right of an ordinary citizen. I have made money here and if a loyal heart or a willing hand should be required to defend the country mine would be one of the first. But when my son, who is an Australian native, applies for an entrance to a Military College, his application is rejected for no other reason that that of colour. I was prepared, and could afford, to pay all expenses and made personal application to the Minister for Defence, but was told that the blood of an Asiatic flowed through the veins of my son. His mother was a European, the boy was physically and intellectually fit but to my great disappointment my request was refused.

Still, I am loyal to Australia, and the Defence Department has my offer of the use of 500 camels, and some horses, as well as my own personal experience.

… I have suffered a number of hardships under the White Australia policy but am now quite independent. I, of course, would not like to see this beautiful country flooded with cheap labour, but rather than block a man from entering the country, because he happens to be a different colour, I would inquire into his qualifications, and, if he was worthy admit him, with full rights of citizenship.

Although there has been a rejuvenation of interest in the role of the camel and the cameleer in Australian history, it is largely an unfamiliar footnote that is rarely discussed. Within this footnote hides Abdul Wade. In various books and articles on the cameleer there is a line, paragraph or at most, a few pages dedicated to his contribution.

Despite his prosperity Mr Wade could not fight the modernisation of Australia’s infrastructure. The development of roads and cars saw the redundancy of the cameleer as the conveyers in the Outback. Previously a cornerstone for transportation, the camel quickly became a “noxious animal” that should be shot at sight.

The passing of the Camel Destruction Act in 1925 made it illegal to possess unlicensed camels which forced Wade to sell his breeding stations. His prized camels were either released into the wild or shot.

After his wife Emily Ozadelle died in 1926, Mr Wade forfeited his Australian citizenship and moved back to Afghanistan. While his loyalty and generosity was appreciated sporadically in old Australian newspapers during the '30s and '40s, he was seen as an anomaly, never really fitting in.

According to the Australian Dictionary of Biography his children continued to live in Sydney and his son Abdul Hamid fought in the Australian Navy in WWII.