Impure. Polluted. Untouchable.

These are words that are used to describe a class of Nepalese people known as the Dalits.

The Dalits live at the bottom of Nepal’s traditional social order, known as the caste system, a 2000-year-old Hindu custom that violates civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights by many international standards.

While recent political and constitutional changes have seen the Nepalese government take steps towards resolving the entrenched practice of untouchability, in the villages of rural Nepal, discrimination against Dalits continues.

Untouchable orphans

Arjun, Deepika and Susmita Pariyar are siblings. They live in the village of Chiruwa, near Pokhara, in central Nepal. They are orphans and Dalits.

The children were abandoned by their parents. Their father was an alcoholic who would beat their mother. Fearing for her life, she fled.

Soon after, their father disappeared too.

The Pariyar children: Susmita, 13, Deepika, 9, and Arjun, 11. Photo: Corinna Lagerberg.

While the community of Chiruwa have banded together to help the family, Susmita, 13, knows she is still treated differently to the other children in the village.

“We only get given food in exchange for work but we feel uncomfortable asking for work,” she says.

“It is also hard for us to find work because we can not enter people’s houses to help with chores like cooking and cleaning.

“Also because there are three of us it is even more difficult to get food and it is very hard for me because I am the eldest and I feel responsible for my brother and sister.”

When asked if they are happy in their village the Pariyar children do not know how to respond.

“We feel sad that we are different,” Susmita says. “Why can’t we go inside the houses?”

The Pariyar children’s home is a small clay hut. It contains a broken bed, some donated clothes, blankets and a shelf of small possessions.

There is no electricity, no bathroom and, due to a lack of insulation, even a fire at night is not enough to keep them warm.

Arjun, Susmita and Deepika’s bed, the blankets have been donated by community members. Picture: Corinna Lagerberg.

Despite following some traditional caste practices, the community of Chiruwa is beginning to break down social barriers by helping the Pariyar siblings.

Community members help pay the children's school fees, donate uniforms, provide food and even give financial donations.

Neighours Rosni and Subin Magar are two of the villagers providing help, despite their middle caste ranking.

“It was difficult to help the children because of the caste system. There are many rules and practices which we must follow,” Mr Magar said.

“It is difficult because the children cannot come inside [the houses] so they cannot help with cooking or chores.”

But for the Magars, conforming to the practice of untouchability is about keeping up appearances.

“We do not care about the caste system, for us it would not matter if the children touched the water or came inside the house, but society does care and we do not want to cause trouble,” Mr Magar said.

Rosni and Subin Magar decided to overlook social stigmas when helping their neighbours – three orphaned Dalit children. Picture: Corinna Lagerberg.

Changing laws, but entrenched practices

Nepal’s new constitution, enacted in 2015, aims to do away with the discrimination and untouchability directed at Dalits such as the Pariyar orphans.

Previous constitutions had barred discrimination based on sex, religion and race. However, no laws and regulations specifically covered discrimination based on caste until changes were included in the 2015 constitution.

According to section 24(1) of the constitution:

No person shall be subjected to any form of untouchability or discrimination in any private and public places on grounds of his or her origin, caste, tribe, community, profession, occupation or physical condition.

Other sections of article 24 make reference to access to public places and services, production and purchasing of goods and services and demonstrations of superiority and inferiority based on caste.

The Nepalese government had also previously taken legislative action to prohibit discrimination against Dalits, including the the Civil Liberties Act of 1954, section 10A of the Civil Code, and the establishment of the National Dalit Commission in 2002.

Today, at least on paper, Nepal’s legal protections against anti-Dalit discrimination appear strong.

But despite these measures, caste-based discrimination remains a central feature of life and social interaction in Nepal.

Like many South-East Asian countries, Nepal has ratified the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD).

By signing the convention, Nepal is obligated to provide effective remedies for acts of racial discrimination, including violent attacks.

Infographic by Corinna Lagerberg.

However Dalits are frequently victims of targeted assaults. Police officials can fail to investigate reports of violence against Dalits and perpetrators of attacks on Dalits often go unpunished.

Dalits are routinely prohibited from entering upper-caste Hindu temples and have been penalised for marrying above their caste.

They are forced to work menial, dirty and hazardous jobs, with many subjected to bonded labour, despite its outlawing in 2002.

All such acts of discrimination and exclusion are prohibited by the ICERD, which requires parties to the convention to “pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating racial discrimination”.

But NGOs have not seen obligations under ICERD honoured and are concerned that due to the difficulty associated with implementing the new constitutional provisions little will change.

The International Dalit Solidarity Network, a network of international human rights and development agencies that advocate for Dalit rights, is sceptical about the enforcement of the new constitution.

“Experience in caste-affected countries shows that guaranteeing rights on paper is not enough, and strong implementation and enforcement is critical.”

“Despite the fact that caste discrimination is prohibited … implementation is the main problem.

“Numerous reports, statistics and case documents [show] persistent patterns of discrimination against Dalits.”

A host of United Nations treaty bodies have released reports documenting systematic violations of Dalit rights over the last decade, although statistics since the implementation of the new constitution are yet to be collected.

According to the IDSN, the Nepalese government has not implemented additional policies to ensure that the protection of Dalit rights under the constitution are secured.

“Perpetrators often enjoy impunity for acts of exclusion and heinous crimes against Dalits and many cases are never registered due to threats by dominant castes and negligence of the police.”

The Pariyar children's possessions – all have been found or donated. Picture: Corinna Lagerberg.

Discrimination against millions

According to the 2011 census, the Dalit caste constitutes 13.6 per cent of Nepal’s population.

But Dalit scholars and leaders believe this figure to be closer to 20 per cent, with the discrepancy due to fear of discrimination if identified as a Dalit and flawed census methods.

This means that at least 3.6 million Dalit people rely on the protective provisions of Nepal’s constitution on a daily basis.

However, according to Manoj Lamichhane, a member of the highest caste and a high school teacher at Shree Arniko Secondary School, located 300km west of Kathmandu, the new constitutional provisions have been even less effective in rural areas.

“In the villages the practice of untouchability is very much alive,” Mr Lamichhane says.

Mr Lamichhane has seen the reluctance to abolish the caste system first hand, with young students voluntarily choosing friendship groups and even class seating arrangements based on caste.

“People believe that because our forefathers have practiced this tradition we must continue with it,” he says.

“Because of these attitudes I think it will take a long time to abolish the caste system.”

But Mr Lamichhane does not believe the law is the most effective way to tackle the heavily ingrained practice.

“We first need to pay attention to how we teach and educate people to disrupt the normalisation of this system, something I try to do in my classes,” he says.

“I think the best way to abolish the caste system in villages would be to make people understand that everyone is a human being. We ourselves have made the caste system, no one is born as a Dalit or a Brahmin [highest caste].”

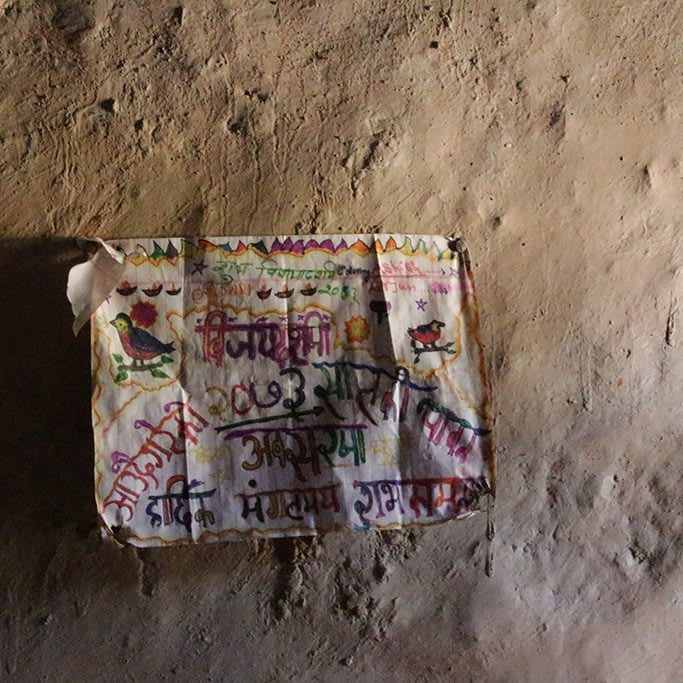

A picture drawn by Deepika to decorate their home. It wishes all who read it a happy Bijaya Dashami, the largest religious festival celebrated annually in Nepal. Picture: Corinna Lagerberg.

A life of hardship

The Pariyar children of Chiruwa live in abject poverty, relying on the generosity and employment opportunities offered by higher caste neighbours for their very survival.

Living conditions like this are a common factor in the life of a Dalit and play a key role in the discrepancy of life expectancy between the lowest and highest caste, averaging at 10 years.

Like many Dalit children, it is unlikely the Pariyars will complete their School Leaving Certificate or higher, with the most recent Nepal Living Standards Survey recording Dalit completion of the Certificate at 3.8 per cent compared to a national average of 17.6 per cent.

And once the Pariyar children enter the workforce things are not set to improve.

It is likely Arjun, Deepika and Susmita will resort to wage labour, an industry comprised of over 60 per cent Dalits.

According to the International Labour Organisation a Dalit worker will receive on average Rs 96 (AU$1.17) for a day’s work, with the mean wage for a female worker Rs 78 (AU$0.95) and Rs 99 (AU$1.21) for a male worker.

Despite the discrimination they face in almost every aspect of life, the Pariyar children cannot imagine the world functioning any other way.

“This is all we have known,” Susmita says.

The children explain they have experienced no difference in treatment since the introduction of the new constitution.

“We try not to have any feelings towards the rules of the caste system, about not being able to go inside houses or touch water, it has been this way as we can remember and nothing has changed.”

When asked if they believe the caste system will ever be abolished, the Pariyar children answer in unison: “No.”