Read the Charter of Independence here.

BY STEPHANIE STAMATELATOS

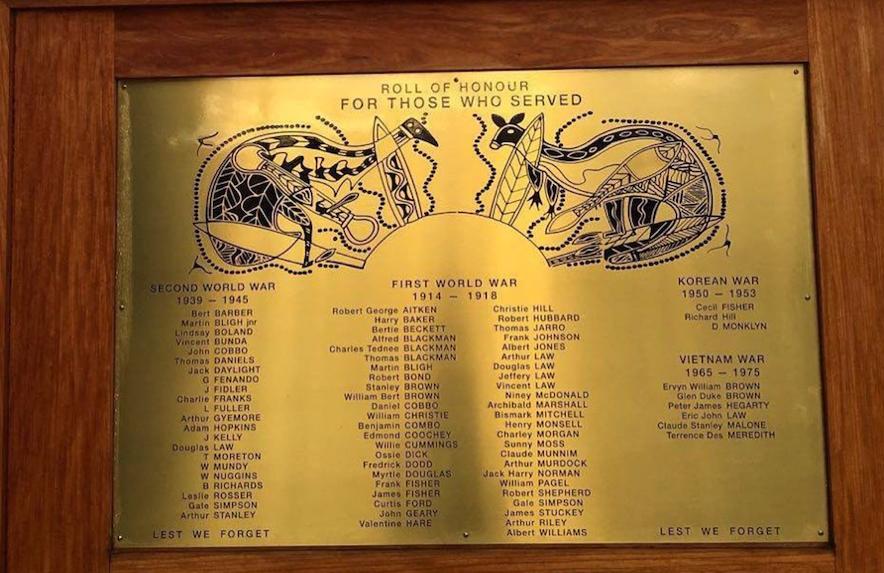

On a recent visit to Geraldton's war memorial in Western Australia, Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt was surprised to see the names of three Indigenous veterans he had not encountered before.

As the first Indigenous member of the House of Representatives, elected by Western Australians in the seat of Hasluck, he is familiar with the names of the state's Indigenous veterans.

They are all listed in No Less Worthy, a publication acknowledging their contributions to the World War I effort.

Mr Wyatt said Indigenous Anzacs’ lack of citizenship at the time of the Great War has left some of them unrecognised, even today.

“We’ve still not done enough to recognise the service of Indigenous people in every military campaign,” Mr Wyatt said.

“Fellow veterans saw them not because of the colour of their skin, but because of their mateship and because you could rely on them to cover your back.”

With Geraldton in mind, he said there were a “number of people in country towns who aren’t listed on the records”.

Other than not being formally recognised through citizenship, Mr Wyatt said he thinks the disappearance of many veterans in battle could be a possible explanation for their absence from the records.

But this reality is not limited to Western Australia.

Sydney resident Kayscha Corcoran often attends the annual dawn service in Ulladulla.

After last year’s service, her family noticed an Indigenous ceremony on the harbour foreshore.

“Later we were told that [Indigenous locals] hold their own service to remember the 17 Indigenous soldiers from the area whose lives were lost...yet they aren’t recognised to this day. They aren’t included on the honour rolls,” Mrs Corcoran said.

She said that information left her feeling “disappointed” and “angry”.

The Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial lists the men and women who have died in the service of the nation.

But even some Indigenous veterans who died in World War I and are formally recognised in their home towns cannot be found on the Roll of Honour.

Australian War Memorial Indigenous Liaison Officer Michael Bell attributed the inconsistency between national records and country town records to a “not one size fits all” explanation.

He said Indigenous veterans may not be recorded on the Roll of Honour for a variety of reasons, such as “racism or unawareness of their service”. But added that ultimately, “we don't know”.

Mr Bell is predominantly responsible for researching and identifying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander servicepeople, alongside a team of researchers.

“If they contact me, I can do the research. If they have been left off, we can have them added,” Mr Bell said.

“It’s all about working with the community to show what we’re doing at the War Memorial.”

In March 2019, the Australian War Memorial unveiled the “For our Country” sculpture to commemorate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians' military service.

Member of the Stolen Generations Kerrie Shurley described the sculpture as “a great way to increase the conversation about that part of our history”.

She said educating more Australians about Indigenous participation in military conflicts is a crucial step towards acknowledging unrecognised veterans.

“Lots of people I’ve spoken to don’t know the circumstances and amount of their involvement.”

The Western Australian branch of the RSL (RSLWA) banned the Welcome to Country ceremony and the flying of the Aboriginal flag at all of its Anzac and Remembrance Day services in February.

However, this policy was withdrawn a few days later.

Indigenous Australian Mick Bonner was “heartened” by the backlash following RSLWA’s initial decision.

“It symbolises that Indigenous people can be a part of this sacred day,” Mr Bonner said.

“I think the key to telling the stories of our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander soldiers is including it in our education system whenever we talk about Anzac Day.

“Until that happens, the general public won’t think about Indigenous soldiers.”

His documentary titled “Soldiers not Citizens” was due to be released this year but has been postponed due to COVID-19.

Owner of Sacred Era Michael Weir agreed with the correlation between educating others and recognising Indigenous veterans.

Sacred Era is an online business which sells the popular “Black Anzac” t-shirt and is rooted in Mr Weir’s passion to “continue the fight for our mob”.

With every purchase of the t-shirt, customers also receive stories of Indigenous veterans.

The idea is for the t-shirt to spark conversations amongst both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians and result in “a handshake, a hug, a nod…a small sign of respect”.

“Acknowledging Indigenous Anzacs tells our youth that we matter, that the country cares about them, that they are someone,” Mr Weir said.

Australians placed candles in their driveways at dawn on Anzac Day and stood for a minute of silence to honour all servicepeople.

Ken Wyatt said he will never forget the “immense pride” on the faces of Indigenous veterans as they led the national Anzac Day march for the first time in 2017.

To this day, the Indigenous community hopes generations to come will discover the legacy both recognised and unrecognised Indigenous Anzacs left behind.

Lest We Forget.