Read the Charter of Independence here.

The enemy of my enemy is my friend.

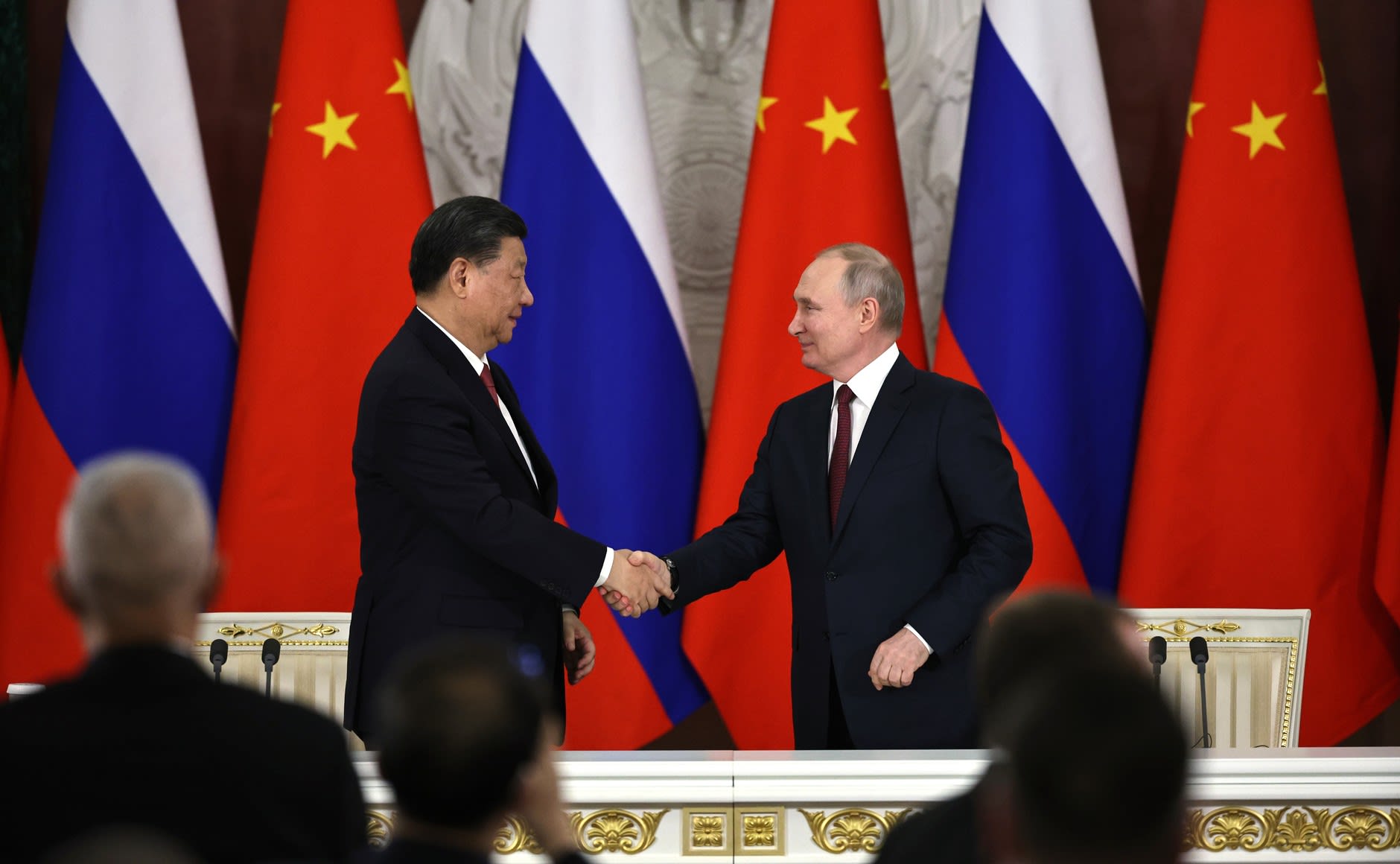

That seems to be the attitude that China and Russia have towards each other, experts say, as Xi Jinping’s China and Vladimir Putin’s Russia develop ever-closer ties to contest the unipolar world that the United States has enjoyed since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The relationship between China and Russia has long sparked fascination. From the Russian expansion into Chinese Manchuria in the 18th and 19th centuries, through a strengthening of relationships after World War II as powerful leaders of the communist movement, and to a dramatic Sino-Soviet split only a decade later, the dynamic between the two nations has profoundly impacted global affairs.

Now, as experts point out, even though there is no formal alliance between the two nations, they are building a closer and more productive relationship to collectively challenge the US-established Rules-Based International Order (RBIO).

Putin made a two-day visit to China last month to further enhance the strategic relationship between the two countries. The meeting was seen as a veiled challenge to US and Western influence in the Asia-Pacific, representing the world’s shift to a more uncertain, multipolar world, AP reported.

The growing relationship between Russia and China “needs to be on our radar” when it comes to security in the Indo-Pacific region, according to Dr Alexey Muraviev, an associate professor of national security and strategic studies at Curtin University, in Perth.

Muraviev told a Curtin-RMIT University seminar last month that although Russia and China are not officially allies, many of their actions in recent years, especially with regards to their military, can be construed as a productive strategic partnership that can only be compared to “what joint allies do”.

“Together, China and Russia have the world’s largest combined military standing force,” said Muraviev, who has published widely in the field of national security, strategic and defence studies.

The two countries already hold joint activities in the Pacific region such as military exercises in the Sea of Japan — actions that Muraviev said “can’t be ignored” due to Russia’s military capability.

“Russia can be the barometer as to how China advances militarily”, Muraviev said.

In relation to Australian security, he said Russia and China are "definitive" in how they look at the AUKUS trilateral partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom and the US as "a geopolitical construct” that threatened to undermine regional peace and security.

This alliance has serious ramifications for the Western-led world order, which Australia is firmly committed to, he said.

Apart from growing military interactions, Muraviev noted the increase in Russia-China trade relations in the last five years, which he said “can no longer be dismissed”. Such trade has especially increased since the war in Ukraine, with China now being the main consumer of Russian resources due to Western sanctions. In 2023, Chinese trade with Russia reached a record high of $240 billion.

This is significant as it reduces the impact of Western sanctions on Russia, allowing the nation to continue to wage war in Ukraine through China’s support of Russian exports.

Diplomatically, Muraviev said that this alliance has gone “way past" the standing of strategic alliance, with Russia and China meeting each other frequently for diplomatic visits.

“Russia is the most frequently visited nation for Xi … There is clearly a personal affinity between Xi and Putin that goes beyond diplomatic etiquette.”

Some scholars have taken a more cynical view of the alliance. Austin Harris, a Monash Masters of International Relations student, said such a partnership does not help civil society in either country.

“Alliances with no limits are not really going to solve the systemic social, political, economic and diplomatic problems that both China and Russia are going to face,” Harris said.

He said the alliance has hurt people in Russia as well as those in Ukraine “suffering under the leadership of an authoritarian, kleptocratic state led by Vladimir Putin”.

“[Russia’s] partnership with China is allowing that kleptocratic regime to cling to power and continue its depredations of the Russian people themselves and the 50,000 people that have died in the [Russo-Ukraine] conflict already.”

Like Muraviev, Harris noted the increased trade relationship between Russia and China, ending the unipolar dominance that Western economic systems and the US have enjoyed since the 1990s.

Harris said: “The real question here is: are we going to shift to this bipolar world order in which countries are left to choose between keeping dollars or yuan as their trade medium of choice, which doesn’t necessarily bode well for Australia?”

He said in the eyes of both Russia and China, “Australia is just viewed as the West”, particularly with military partnerships such as AUKUS.

“It is effectively an unsinkable US ally, which makes it very much an enemy in Russian and Chinese strategic planning,” he said.

The two most powerful authoritarian regimes posed major security risks domestically for Australia too. "We are well aware of disinformation and misinformation tactics that are used by Chinese forces, by Russian forces, which are hostile to the democratic values of a state like Australia.”

However, other scholars argue that Australia needs to stop viewing countries like China as a security threat.

Dr Gerardo Papalia, a Monash University research affiliate who specialises in diplomatic affairs, said Australia should move away from being a staunch ally of the West, in this shifting world.

"I wouldn’t frame Australia’s relationship with Asia as an issue of security; I think it’s a cultural issue," Papalia said.

The negative ideas that Australia associated with the alternate powers of China and Russia were only "self-damaging" for Australian interests, he said.

"If China thinks we’re going to create trouble because of our alliance with America, they will say that they shouldn’t rely on Australian products anymore," Papalia said.

"The more we create an attitude of distrust between us and China … the more China will say, 'I’m big enough to go somewhere else’."

Papalia instead urged Australia to embrace and engage with this growing dynamic between China and Russia — to be a "part of that game too", rather than simply follow America’s wishes.

"We don’t necessarily have to see China and Russia being closer as an obstacle for exchange and understanding," he said.

"As Australians, we don’t necessarily have to see ourselves as having to go along with Great Britain or go along with America."