There's nothing like the sound of a good baguette. The crunch of the hard crust, to the opening of the soft, fluffy middle.

To some, that sound came at a cost.

The French invasion and occupation of Vietnam was long and painstaking. Arriving in the late 1800s, France took root and left their Eurocentric marks on Vietnam until the mid-1900s — including but not limited to: tobacco, religion and, of course, the baguette.

For those of you still living under a rock, the baguette is the outer casing of one of the world’s greatest delights, the banh mi.

The dish, meaning 'bread' in Vietnamese, often referred to as a sandwich or roll, consists of pickled julienned carrots and radish, cucumbers, chillies, cilantro, your choice of protein, mayo and pâté.

As a vegetarian girl myself, I opt for fried eggs (and no pâté), but that’s just me.

It’s interesting, albeit unsettling, that imperialism led to the creation of the now classic Southern Vietnamese street food.

While the French inhabited the region, they introduced rich and expensive food that the average person couldn’t afford.

As JY, chef and co-owner of Ca Com Banh Mi Bar in Richmond, says, the banh mi "is an evolution of the French jambon [sandwich]”.

The Vietnamese found what was accessible and made the banh mi their own. What once was butter is now mayo. What once was cured ham is now cold cuts. The evolution has continued as cultural diversity is more accepted and introduced to areas previously without such cuisines.

It’s no secret that the banh mi is a staple in the Melburnian diet.

Many locals have a favourite banh mi spot they think is the best. (For me, it’s Ca Com Banh Mi Bar.) And with half a dozen banh mi places in any given area, seemingly all within a kilometre of each other, it’s not hard to integrate it into our lunches.

While Vietnamese food is not native to Australia, Melbourne has one of the largest immigrant populations in the world. And such a place that thrives on diversity, so too do our stomachs.

Over the past decade, the banh mi has risen in popularity on social media and on menus. This demand has created more restaurants that feature the banh mi.

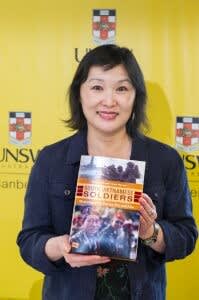

There is a logical increase in the number of banh mi joints in Melbourne, explains Monash University Professor of History Nathalie Nguyen, “because the refugee community is quite substantial".

"The two largest centres of [the refugee] population are Sydney and Melbourne,” she says.

After the fall of Saigon in 1975, the Vietnamese diaspora began to spread. Between the 1970s and 1990s, there were a few great waves of migration, but it wasn’t until recently that this sandwich started to take over.

The first generation of refugees that arrived were largely labourers and worked tirelessly for their future generations. And as the community has laid its foundations in this city, those future generations are now spreading their culture through these delicious stuffed rolls.

The increasing esteem and perhaps adoration of the banh mi should not go unnoticed, and nor should its history.

The banh mi represents a lot more than just a sandwich. As the migration from Vietnam continued, so too did anti-Asian sentiment. And while “the scars of that will probably go on,” Prof Nguyen says, “I think most Vietnamese would feel very proud of the community”.

“Before 1975, there were only about 1,000 Vietnamese [refugees] in Australia,” she says. But now they serve as a successful example of a community that has settled in. Their influence on food and culture in Melbourne is vast and undeniable.

A new problem banh mi masters are facing is the reputation of the sandwich. When a product is made well, it’s going to cost a little more. While the banh mi is a classic Vietnamese street food, it has become so much more in Melbourne.

‘Artisinal’ or ‘craft-made’ sandwiches exist, for exorbitant prices one could argue.

JY explains that food outlets are pushing up prices because it "reflects more of the value we place on ourselves and our heritage — and that we deserve to be treated in the same way as our contemporaries, as a Reuben sandwich [for example]”.

Nowadays, the banh mi should be on par with other sandwiches out there.

The legitimacy of the banh mi is continuing to grow — not just in our diets, but also in our dictionaries.

In 2011, the Oxford Dictionary added the term 'banh mi' to its platform, defining it as follows:

“In Vietnamese cuisine: a sandwich comprising a baguette (traditionally baked using a combination of rice and wheat flour) split lengthwise and filled with a variety of ingredients, typically including pâté and/or grilled meat, pickled vegetables, sliced chilli or chilli sauce and fresh coriander.”

In 2022, the Merriam-Webster dictionary also created an entry for the term.

This addition is important as internationally recognised foods become more integrated into Australian society.

The history of the banh mi is integral to its creation. And with every bite, juicy and delectable, it must not be forgotten.